Systematically producing, organizing, and managing content in a way that supports strategic goals

Author: remap_content_admin

-

How to write About page copy

Ok, I am back from Germany. And one of the first things I did when I got back was to speak to a brilliant, young solopreneur about her business. Her About page came up: How to write one?.

And on further reflection, I get this question a lot. Maybe once a week or so.

Here’s a good place to start – think about the questions you get that an About page should answer. They come in human language like this and are usually straightforward:

- What are you up to nowadays?

- What do you? What does your business do?

- How did you get into that business?

- What’s your background?

These questions should all be pretty well covered in your About page and/or your Now page. But how?

By understanding that an effective About page is built on a strategic framework. To be precise, your About page should have at least 3 and up to 5 key components:

- Purpose, which includes your vision, mission, and values

- Story

- Bios

- Just the facts

- Now

Let’s jump right in. And by the way, these are arranged in order. If someone visits your about page, take the chance to tell them why you exist first. Then your story, and so on. They’ll find the contact info if they need to.

What is your purpose?

Simon Sinek wrote a book about this (Start With Why). Corporate marketers call this, “brand purpose”. Peter Drucker and dozens of other business thinkers address this in a different way, by encouraging us all to view our business as something more than a mechanism for making money by exploring three concepts: Vision, Mission, Principles. I absolutely encourage all of you to know your Vision (the future state you want to create), your Mission (your business’s role in creating it), and your Principles or Values (what you believe in).

If your looking for “who invented it?”, the true answer is always someone in Ancient Greece – and usually in a more thought-provoking and directly applicable way than any contemporary business pundit. Having said that, the idea of identifying business purposes really belongs to Peter Drucker.

It’s the foundation of your About page copy – but it’s not necessarily viable web copy. Go through the Vision Statement / Mission Statement / Values exercise, but distill down to stating your purpose. We exist to make this future status quo a reality.

Tell your company history

Some would say, “tell your story” but that’s a bit vague. Donald Miller wrote a book about this making the case for framing this as story branding; the book holds that the strongest way to create a brand identity express its significant parts as a narrative. Some of the things you can highlight here are “Who it’s for?” and “What It’s For?” (the central questions in Seth Godin‘s masterpiece, This is Marketing: You Can’t Be Seen Until You Learn to See.((Of all the books cited in this post, This is Marketing is the one to read))

In other words, use your story to elaborate on your positioning. Philip Morgan has written an excellent book on positioning for “technical firms”, by which he means dev shops; it’s largely applicable to knowledge worker-based B2B businesses. A great way to make the transition from an internal memo to a viable copy is to write your positioning into your story.

Provide a biography(s)

This is collapsible and expandable, like a telescope. Try writing these as LinkedIn taglines first (about 3 to 10 words), then copy and paste the taglines back into your website and expand on them, keeping continuity. The website provides you the space for some personal touches, which can also be addressed in a Now page, as I discuss below. I have no author to cite here; when in doubt, cite William Strunk Jr’s Elements of Style. Why? To curb the instinct for talking too much about ourselves.

Provide non-personal facts

For larger companies, provide information about the company, your clients, your industry, or even logistical stuff like your street address. Your horizontal specializations and skills figure in here. Most About pages are some souped-up version of this element packaged together with company history. This is quite similar to the concept of providing an “Orientation Manual” about your business, which I have written about recently. An idea inspired by David C. Baker.

Provide your “Now”

A Now page is a marvelous framework for communicating useful information about yourself in a business context. It answers the question, “What are you doing now?”, in a way that a conventional About page or LinkedIn profile often do not.

You can create a Now page on behalf of key individuals within a firm or on behalf of the aggregate “now” of the company. But it was developed with the individual in mind, by Derek Sivers himself.

The last item on the list was conceived as separate to a Now page – and it certainly can be. Whether you make it part of your Now page or separate, two things:

- Write them at the same time

- Let the Now page be update and easily updatable – by keeping it brief.

That should be more than enough to get you started. If you do create a Now page, reply to this email and link me to it – I’m curious! Here’s mine https://www.rowanprice.com/now/

My best

Rowan -

Psychographic Positioning

Back when I was in the old world – last week – I touched on sizing and segmenting markets (plural) for your products and services using psychographics((“Understanding the people in your market by assessing long-term emotional realities, values, opinions, mindset, interests, and lifestyles” https://www.rowanprice.com/dictionary/#psychographics)), which sets itself apart from the standard segmentation approach: demographics.

Demographics groups people by external, easily quantifiable characteristics, such as age, race, sex, employment status, education level, income, relationship status, and more. But more than that, it looks for averages and medians within groups – what’s the average income of Californians? Or the average lifespan of dog owners.

B2B marketing takes that approach and applies it to companies, usually by employee headcount and estimated annual revenue:

Salesforce.com is the CRM for enterprise and SME sales forces” [meaning really big]

Note: Salesforce is so huge and established, its positioning is really just, “CRM software”. But the rest of us have to be more demographically specialized.

Demographic Positioning

Vertical. The classic (and hardest yet most effective) approach to demographic positioning is to position by “vertical”: Arete provides “Mission-critical custom software for higher education”

Horizontal. By “horizontal” (skill) specialty: Fair Winds, provides, “Kubernetes Container and Cluster Infrastructure, built and managed by a team of experts.” (Kubernetes is a type of cloud infrastructure tech)

Platform/technology. By platform: North Peak is “Your Trusted Partner for Salesforce® Nonprofit Solutions” (that’s sort of a combined platform-vertical positioning)

Audience. And by audience: Optimize my Airbnb provides: “Danny, the best in the world at Airbnb.”

The last one, audience, you might call miscellaneous. It’s positioned to a demographic group of people (AirBNB hosts) that doesn’t fit neatly into a vertical. And it’s not really a platform. It’s a group of people who do something or have something in common.

These are all valuable ways to think about positioning. There might be other ways to slice and dice demographic positioning, too. And other categories you could invent, such as Productized Service (example: Case Study Buddy), which would be a close cousin of horizontal positioning, just as audience is a close cousin of vertical positioning.

But…

What about psychographic positioning?

But the point is none of the examples above are psychographic. “Audience” gets the closest, but it’s about what happens on the outside (becomes an Airbnb host), not what happens on the inside over the long-term.

We tend to think of psychographics as the foundation for effective marketing techniques, for better copy, better UX design, color patterns, etcetera. Millennials are this. Boomers are that. Lifestyle. Values.

And we adjust the customer experience design accordingly.

But if we take the time, psychographics becomes – or can become – the basis for our de facto positioning.

A common positioning technique is: take your 10 favorite clients of all time and determine what they have in common.

Sidebar: this is yet another exercise that works equally well for product and services firms. Again – products and services are the same exact thing; they are just two different labels you put on the value you deliver. (Reply if you disagree, I could be wrong. Or at least I have been many times in the past.).

Anyway, this exercise usually takes place using demographic thinking. You list your 10 best clients, then start documenting their externally visible characteristics – headcount, location, industry, thing you do.

Psychographic positioning deepens this approach by asking you to look internally. What are the opinions, mindsets, values, and interests of the owners and other buying decision-makers at your favorite firms?

The commonalities you find there might give you much more nuanced positioning ideas than you get from plain old demographics.

Speaking of psychography, it’s nice to be back in the Pacific time zone. The nearby ocean seems to have a calming effect and I feel relaxed. Hope you do too.

My best,

Rowan -

Psychographics and Addressable Market

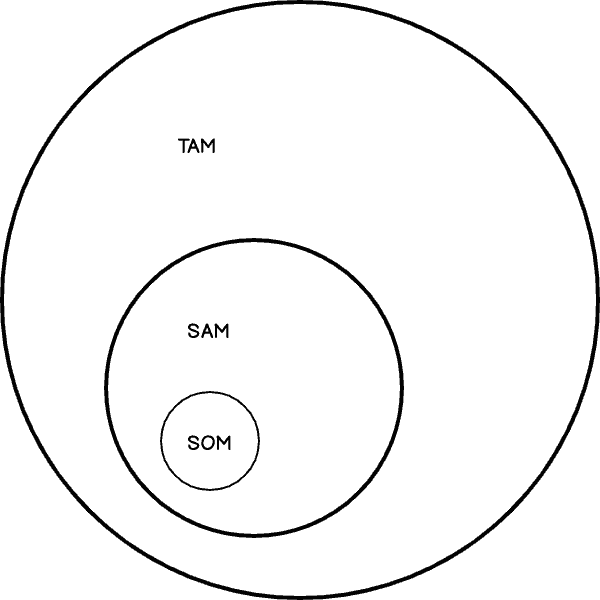

The best way to follow up an article about TOFU, MOFU, and BOFU is to present my other friends – TAM, SAM, SOM. Is it possible that my travels this week have knocked a screw loose? Yes, but TAM, SAM, and SOM are important marketing concepts.

And it’s interesting – and in yours and my shared interest – to think about them in terms of psychographics, not just demographics. That’s my monkeywrench thought of the day and I’ll return to it but first some nerdsplaining:

- TAM = Total Addressable Market

- SAM = Serviceable Addressable Market

- SOM = Serviceable Obtainable Market

Usually, that breaks down into something like the following: enormous TAM, small SAM, and microscopic SOM. The idea here is to draw a distinction between the theoretical size of the market for your products and services and the real size – to which you are able to (a) logistically provide services to and (b) convert from potential customers to partners.

To take a simple example, if you are a solopreneur editor and proofreader for US-based attorneys, the TAM for your services is about 1 million (yes, there are that many licensed attorneys!).

“Oh boy, 1 million potential customers.”

This is the part where the “sharks” on SharkTank roll their eyes. Because there’s no way a single legal editor can provide services to 1 million customers.

So how many licensed attorneys can she address? Even if she productized her service using a 100-person team of subcontractors all equipped with NLP text-editing software, she couldn’t even address a fraction of the market.

The latter scenario, the AI-assisted 100-person legal editing firm, her SAM is a tiny fraction of the TAM – perhaps 3,000/year at the most.

Then there’s the question of obtainability. It’s not just a sales question, but an operational question too. To build a team of 100, you need multiple managers, a finance person, a CTO, a COO, and a remarkable HR person.

You also need capital and cash flow. And then you need to market and sell your services. So of those 3,000 in your Serviceable Addressable Market, you end up with maybe 500 attorneys you can do business within a given year. And that might be a spectacular year.

That’s how you start with a Total Addressable Market of 1 million and end up with 500.

I think the entire framework was invented by someone who got sick of hearing the cliche, “the market for that is is huge”. The TAM market, maybe but not the SOM.

The addressable market theory makes the question, “What’s the market size?” invalid at worst, and inadequate at best.

The Psychographic Dimension

As precise as the addressable market theory is, it has an unseen dimension: psychographics.

I define psychographics as understanding the people you want to help by assessing their emotional realities, values, opinions, mindset, interests, and lifestyles. And for people selling expertise in the form of complex products and services, it’s extremely important.

It’s certainly important in B2B sales and as in B2C. In either scenario, one of the key psychographic qualities is:

Wants to transform

vs

Wants to optimize

In broad strokes, what most people want is to optimize. Fewer typos. More traffic. More efficient billing.

Which is fine; many fortunes have been made in pursuit of optimization.

But in transforming, the stakes are higher. The buyer who wants to transform from present state to future state is looking for deeper engagement, more results, and thus is willing to invest more.

This is the subtlety lost on most lead generation agencies. It’s not about converting more customers to MQLs or SQLs. (marketing/sales qualified leads ). Unless you’re in the business of optimization.

So as you can imagine, it’s important to figure out which business you’re in – are providing optimization or providing transformation? Once you know that answer, you’re on the path to psychographically sizing your market. And maybe better understanding your buyer.

Warmly,

Rowan -

How to think about an editorial calendar

Meet my friends – TOFU, MOFU, and BOFU. Was just joking with a colleague the other day that these sales & marketing acronyms sound more like imaginary Dwarf friends. I knew a guy named Dirthead once, but no BOFU; that’s marketing jargon.

- TOFU = Top of Funnel

- MOFU = Middle of Funnel

- BOFU = Bottom of Funnel (also a great name for a dog)

These acronyms were not invented to describe the funnel in your kitchen but pieces of the conceptual funnel in marketing.

And they are often used in content marketing. Thus, TOFU content is used at the “top” of your marketing funnel, and BOFU at the “bottom”. And so on.

The standard thinking in the design of content marketing strategy is to divide your content into these categories, to ensure strategic allocation of resources.

This brings me to the promise I made a week ago, where I said I’d, “explore the anatomy of a content marketing-focused editorial calendar.”

…

First, though – let me ask a few questions.

Do you hate the term “content” as a descriptor of writing, speaking, creating? I do too. Content is what you put in a jar or a box, not something you create with passion. Yet… it’s also a useful blanket term for the things we create. Jargon is useful and the term content is no exception. So “BOFU content” it is.

Now that we’ve got that out of the way, more jargon questions: do you know what content marketing is? And do you know how it differs from content strategy?

I can be pretty sloppy about using these terms interchangeably, so I think it’s worth it now to pause for a moment and define each one.

Content strategy is the systematic production, organization, and management of all forms of content created by a business entity.

The bigger the organization, and the more digitalized our world becomes, the more sense it makes to have coined this early-aughts concept. Information-rich organizations – libraries, manufacturers, medical schools, city governments, large law firms – produce enormous amounts of content without necessarily using it in their marketing.

But even a small organization like mine, with one full-time consultant (yours truly), a pair of advisors, and a handful of part-time contractors, creates content that isn’t necessarily designed to further marketing. Examples: proposals, creative briefs, ideation worksheets, intake forms, etc.

But one function of a content strategy is to evaluate what to repurpose for marketing. For example, I find it necessary to systematically define my own terms (create a dictionary). Et voila – organizational content repurposed for content marketing: https://www.rowanprice.com/dictionary/

Which brings us to content marketing: content designed to further marketing goals – build trust and create clarity by listening, teaching, and guiding.

Quick aside: is the audience for content marketing internal or external? Both. The first person you have to market to is yourself. You have to get clear in your own head on the value you create; you have to guide yourself, you have to trust in your ability to be of service to the people your business helps.

If anything, content marketing is a subset of content strategy, though again, I fall into the same mental trap as many others by using the terms interchangeably.

…

Back to the anatomy of a content marketing-focused editorial calendar, the easiest way to visualize how you implement a content marketing strategy.

Your editorial calendar is like any other calendar and fits into your work calendar. It tells you exactly when and what kind of content to publish, usually projected out over at least a year-long period. Here’s a very simple example:

- Feb. 4th – publish weekly blog & newsletter article

- Feb. 8th – publish the weekly podcast

- Feb. 8th – distribute podcast announcement via email, LinkedIn, Twitter, and Facebook

- Feb. 11th – publish weekly blog & newsletter article

- Feb. 15th – publish the weekly podcast

- Feb. 15th – distribute podcast announcement via email, LinkedIn, Twitter, and Facebook

- Feb. 16th – record and publish monthly webinar

- Feb. 18th – publish weekly blog & newsletter article

- Feb. 22nd – publish the weekly podcast

- Feb. 22nd – distribute webinar and podcast announcement via email, LinkedIn, Twitter, and Facebook

- Feb. 23rd – publish weekly blog & newsletter article

- Feb. 29th – publish the weekly podcast

- Feb. 29th – distribute podcast announcement via email, LinkedIn, Twitter, and Facebook

- March 1st – publish the monthly case study

In the above example, we see a one-month excerpt from a fairly ambitious content strategy for a 20-person firm. There are 100-person firms that do less. For smaller firms, this is probably too much.

And we also see, in this snippet of an editorial calendar, various types of content (webinar, podcast, blog post, case study) distributed over multiple mediums (email, blog, social media, maybe iTunes, etc).

But we don’t see a strategy. And that’s partly because the strategy depends on you – on what a position of advantage means for you. Remember, I define strategy as deliberately interlocking ideas that inspire a move to a long-term position of advantage.

If you Google around on content marketing strategy, you’ll start to see more TOFU, MOFU, and BOFU. In other words, you’ll typically see some kind of formula that dictates an allocation of type of content and frequency.

60% TOFU

30% MOFU

10% BOFUThis is the huge influence of Hubspot on the content marketing world. As if the proportions of your types of content had to create a funnel shape. And as if the formula for one company matches that of another. In reality, I can’t tell you what your percentage is without knowing the particulars of your business and your goals.

Nor do I think it makes sense to associate one type of content or type of content distribution as inherently bottom of funnel or top-of-funnel. A podcast or a newsletter isn’t necessarily bottom-of-funnel. It depends on what it’s about – is it loosely related to your business but more likely to get views because it taps something universal (top-of-funnel), or is it very specific about how your business is uniquely equipped to solve a problem (bottom-of-funnel).

Apart from case studies, most types of content, or content channels, can help strengthen every part of your funnel. So don’t get caught up in equating one type of content with top-of-funnel and another with middle-of-funnel.

A concrete example of a content marketing strategy

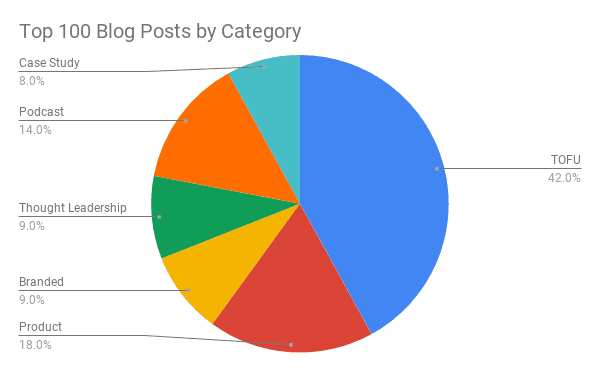

The PPC and SEO metrics company SpyFu evaluated the content marketing strategy of Drift by evaluating postings to its blog over a two year period. Some of the postings were promotions of non-blog post content: podcasts, webinars, case studies, interviews, events, etc. It then classified all that content into 6 categories – TOFU and a few others that basically comprise BOFU and MOFU.

Based on that research, SpyFu was able to say definitively (using their own metrics tool) that:

- Drift’s content marketing was enormously successful, in terms of traffic and engagement

- The success of Drift’s content parallels their publicly reported business success

- 42% of their content was (according to SpyFu’s reasonable classification system) “TOFU”

Does that mean 42% of your content should be TOFU? Not at all. Even for Drift, what worked in 2018 may no longer make sense in 2020. Now that they lead the chatbot-o-sphere in buzz, maybe it’s better for them to focus more on meaty case studies – or deep-dive product tours into how to create chatbots that don’t annoy the hell out of people.

Whereas another software firm – Basecamp – probably needs more TOFU in 2020, something that was hard to imagine in 2007. Pretty much 100% of us inside the digital world at least know of Basecamp. I’ve used it on probably 50 projects over the past 12 years and I don’t even like project management tools.

But what about the broader world’s awareness of Basecamp? After all these years of fame and success, of making the lean, bootstrapped, SaaS business model look attractive, Basecamp now faces challenges from venture-backed upstarts like Monday, which looks like it has more traction. That’s why Basecamp is finally hiring a Director of Marketing ((https://m.signalvnoise.com/basecamp-is-hiring-a-head-of-marketing/ we’ll see how this 180k investment stacks up against Monday’s 180 million in venture fun – most of which is being wasted on Google Ads)) to counter Monday’s multi-million dollar ad spend.

Your business – are you Drift or Basecamp? Should you work on the top or the bottom of your funnel? ((Do you even have a funnel? By the way, the way the funnel concept work holds that you actually have a marketing funnel whether you think you do or not.))

It depends. But I will say this – I wouldn’t sacrifice quality for quantity and variety. So in theory, your minimum viable content marketing strategy expressed as a 1-year editorial calendar will look like this:

- January 31st – publish remarkable, targeted, engaging case study with word-of-mouth sharing potential

In reality, though, it’s not that simple. Because the one thing I haven’t talked about yet is that the more often you publish content, the better your content marketing gets. If you only publish one thing a year, I will bet money it’s going to be less effective than if you publish some kind of content, with some kind of frequency, around that one great thing. That’s partly because high-frequency publishing gets you a little more clear on what helps your audience learn – what format, what length, what subtopics, what frequency, etc.

But even if you can’t marshall the resources to create with consistency, you can design an editorial calendar.

Take action:

- Start with a 50% / 30% / 20% (top, middle, bottom) content marketing funnel. Remember, top attracts new people to your site, middle gets them interested, bottom makes them want to buy.

- Adjust each part of the funnel by 10 to 20% according to your business needs – do you need more people to know about you? Or do you need those who already know about you to become more engaged? Or to actually talk to you about buying?

- Take 5% t0 20% of your annual time and money budget and spend it on content. 5% if you’re coasting. 20% if you’re growth-focused.

- Divide that time and money up into content production assignments over the next 12 months. Make a list of all the kinds of content you want to produce

- At the same time, start marking up a content marketing calendar

- Revise the last two so that they make sense next to one another

I know this is hard work, but you have to start somewhere. Reply and let me know what’s on your new editorial calendar!

My best,

RowanPS. I will be out early next week as I continue my travels but will pick up pen and paper again on Wednesday. I hope this longer than usual post makes up for my absence

-

Why us?

Speaking of unretirement, starchitect Frank Gehry is 91 and continues his daily work – making cityscapes slightly weirder and more interesting. He’s currently overseeing 12 design projects worldwide.

Gehry may be global (I once waited in line for 3 hours to see his newly released Bilbao Guggenheim from the inside) but he won’t work just anywhere in the world. ((http://nymag.com/intelligencer/2020/01/frank-gehry-in-conversation.html)) He says:

“We’ve been asked to do stuff in Saudi Arabia. I went there a couple of times, and they tried to be nice, but it was somewhat insulting. They offered me lots of projects, and they said, “Pick a project, you design it, bring us the design, and if we like it, we’ll pay you.”

That’s not winning without pitching. Amazing that one of the most sought after creative professionals in the world is asked to pitch his work for free.

So it’ll keep happening to us, too, then, even if we build up a body of work as impressive as Frank Gehry’s.

What to do if you are selling complex products or services and asked to give free samples – design comps, product trials, code critiques, analyses of data, lengthy consultations, etc?

Change the conversation. One approach is what Jonathan Stark has articulated better than anyone as the “Why Conversation”. To avoid conflation with the Five Whys Conversation, and to be more precise and less me-focused, you could also think of it the “Why Us Conversation?”.

The conversation answers the question, “Why us: why are our two businesses a good fit for one another – or not a good fit?”

And it gets there through several why sub-questions.

- Why do anything at all?

- Why do that now?

- Why do you want me to help you do it?

The last one is tricky because the answer can be, “I’m not sure yet”. Which is why it comes last – it comes after you have had the chance to discuss the other why questions. Those consist of basic why questions like:

- Why not just do nothing at all? What would happen if you did nothing?

- Why not use an “off-the-shelf” software product to do this?

- Why do this now and not in a year?

And then slightly more advanced why questions, like:

- This project could be costly – why pursue it? Why not just cheap out on Fiverr?

- If this goes well, what will the result be in 2 years? ((Protip: this is related to, if not equivalent to, what Blair Enns calls the value conversation https://2bobs.com/podcast/mastering-the-value-conversation. It takes intangibles though – lots of practice, confidence, and (in my opinion) examples of prior work you’ve done that closely resemble that profitable 2-year result.))

The basic set of questions makes you explain the need to act; the advanced set speaks to the value of taking action.

If you can show that you understand the answers to these questions, then you can talk about the final “advanced why” question:

“Given what we’ve established so far, why do you want my business to help you do this?”

If both sides take the time to work through these answers, a fair fee based on value can be reached without one side having to give something away for free.

What if that doesn’t work?

It may there are too many unknowns to answer the question, “Why us”, especially on the customized services side.

That you can’t say for certain whether there is a good fit. This doesn’t mean there isn’t a good fit, it just means you don’t know whether there is, what it is, and you can’t price it. But you suspect there could be.

If you suspect there’s a good fit, other options can be presented – a productized service or a self-service product. With these options, you are basically saying, “Here’s something that solves most (not all) problems for most people like you.” And it does so at a fixed price that is probably going to be lower than custom services or implementations of software products that are based on a close fit.

For both sides, a productized service represents less risk and less value. It’s also a longer-term way to determine whether a deeper and custom engagement makes sense.

Meanwhile, follow Frank Gehry’s lead and don’t give it away for free. (Yet give away as much helpful, non-customized knowledge as you can).

Yours,

Rowan -

What’s Your Dictionary?

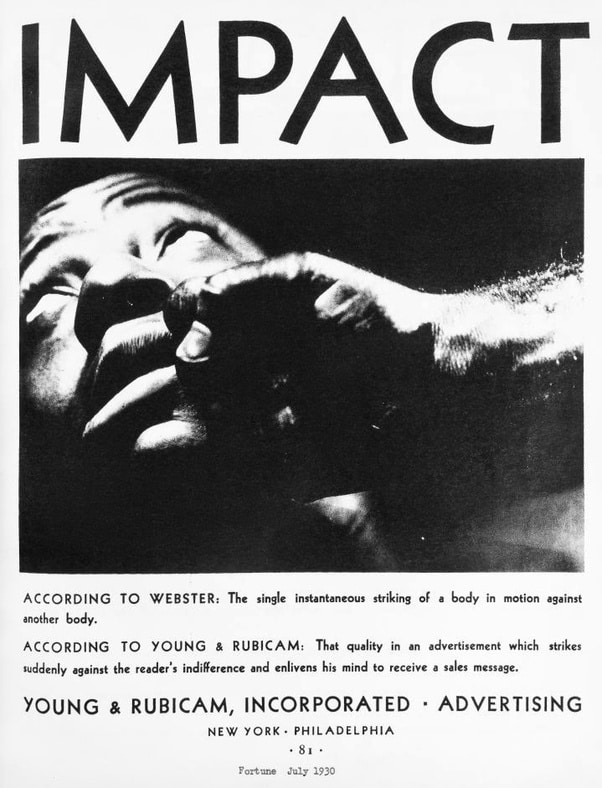

((Raymond Rubicam was one of the only ad agency entrepreneurs to run ads for his own business. He ran ads in Fortune magazine for 30 years. In the ad pictured, he proactively defines a term, rather than letting his reader or Webster decide what it means.

And BTW, he makes a VERY strong case for the value of advertising per se, and for his agency’s ability to exploit it.

One more thing – Rubicam wrote his own ad copy until he was in his 80’s, long after he’d become scandalously wealthy. So never let a consultant tell you that writing copy is “hands work” ))

I have no data to back this up but my gut is that Google is now our most used dictionary.

Or at least our most used dictionary search tool, since Google doesn’t create its own dictionary – instead, it just indexes content from other dictionaries and publishes it at the top of its search results.

One of the dictionaries Google partners to be our de facto dictionary is the Oxford University Press (which now calls itself a “language provider”). ((Google uses Lexico, which uses “language” created by lexicographers at the Oxford University Press. Or at least it uses their definitions, via an API; the “Oxford dictionaries” don’t really exist anymore, or so they say. Except for the OED))

(Sidebar: This is becoming Google’s monopolistic approach to the entire profitable Internet – buy or partner with a successful company, then put that at the top of its search results, defrauding the competition).

The Oxford University Press publishes the mother of all English-language dictionaries, The Oxford English Dictionary (The OED).

The OED is distinct in that it contains not only the etymology of every word in the English language but its first recorded usage. If you think of every etymology as a story, then no book has as many stories as the OED. And understanding these stories, you get a deeper sense of a word’s many shades of meaning.

So Google’s dictionary search results must be amazing, right?

Nah. The search results that the Oxford University Press gives Google are just the minimum viable product, trimmed down to its leanest, most-consumable size in the aggravating style of Dictionary.com or Miriam-Webster online.

Look at the definition of “strategy”, for example, google.com/search?q=strategy:

“a plan of action designed to achieve a long-term or overall aim.”

Pretty stingy, Google and Oxford University Press.

Especially compared that with Harry Mintzberg’s definition of strategy in his book, Strategy Safari:

- Strategy as plan – a directed course of action to achieve an intended set of goals; similar to the strategic planning concept;

- Strategy as pattern – a consistent pattern of past behavior, with a strategy realized over time rather than planned or intended. Where the realized pattern was different from the intent, he referred to the strategy as emergent;

- Strategy as position – locating brands, products, or companies within the market, based on the conceptual framework of consumers or other stakeholders; a strategy determined primarily by factors outside the firm;

- Strategy as ploy – a specific maneuver intended to outwit a competitor; and

- Strategy as perspective – executing strategy based on a “theory of the business” or natural extension of the mindset or ideological perspective of the organization

Now that’s a definition you can sink your teeth into. Learn from.

Can you really do justice to a complex concept like strategy with the short definition Google offers?

No. But dumbing it down is profitable.

((Interestingly, the Mintzberg’s definition of strategy is culled from Wikipedia, which is now a *distant* second place for the search word “strategy”. When there is a profit motive, Google is sneakily finding ways to displace Wikipedia as the #1 search result, a palce Wikipedia has occupied for about 15 years))

What does this have to do with marketing and ideation?

We all use words every day in business, whether we think of ourselves as marketers or not. And those words contain our ideas. That’s why Harry Mintzberg created his own definition of strategy (as I have myself, for digital strategy). In “A Technique for Getting Ideas”, James Webb Young puts it best:

Thus, words being symbols of ideas, we can collect ideas by collecting words. ((James Webb Young also said, “The fellow who said he tried reading the dictionary but couldn’t get the hang of the story, simply missed the point that it is a collection of short stories.” This is in fact the concluding sentence to his book, A Technique for Getting Ideas))

That’s why marketing copy loves statements like, “There’s a lot of confusion about what the term ______ means. People think it means ____, but actually think it means ____”.

Sometimes this is done to try to “own” definitions of business terminology. The way that Joe Pulizzi tries to own the definition of content marketing.

That’s a good marketing strategy in and of itself. But you really can’t do that because there’s never just one definition of any given term. Consult the OED: If a word doesn’t have more than one shade of meaning, no one actually uses it.

You can only own your definition and use it to better communicate your ideas.

And if you have strong ideas about your business, then there are words that will come up over and over. Words like strategy, implementation, analytics, migration, framework, analysis, discovery, etc. And these words are key to your marketing, especially your content marketing.

Have you ever had a conversation go like this?

“Well, wait – what do you mean by strategy in this context?”. Or, “Ok, but how do you define agile?”.

You’d think the answer would be, “Look it up in the dictionary!”

And it may be. But that answer ignores several key points:

- There is no one dictionary-to-rule-them-all and never has been ((And as Abe Lincoln advised, you should always look up a given word in at least two dictionaries anyway))

- You may be using the word in your own way, to describe your own business idea. And your idea might be a little different from someone else’s.

- Many of the complexities of our highly technical businesses just don’t exist in dictionaries.

So instead of saying, “look it up in the dictionary” ((Counterpoint, people should consult dictionaries more – at least as a starting point)) your answer to, “What do you mean by that?” is often you winging a definition. But “winging it” has a negative connotation for a reason.

Just because you know what your idea is doesn’t mean you can describe it in words for me.

So write it down. When you’ve written down your definition of a term beforehand, you go from ad-libbing to sharing your own little piece of intellectual property.

A conversation about complex products and services and how they are used often involves multiple, “let’s define that means” moments. And subsequent negotiations between the parties involved: “Ahh, I see what you mean by dynamic integration now; I have a slightly different definition but let’s use your definition for the purposes of this conversation”.

And it’s not just an advantage in sales; you should also create solid definitions of your business ideas in your marketing copy and content. Each idea a building block for future ones.

That’s one of the reasons I created my own dictionary of terms. ((But the best example of creating your own dictionary is captured in the image that comes with this post. That ad was written by Raymond Rubicam, founder of Young & Rubicam, now a part of the WPP conglomerate, which also owns Ogilvy, along with 600 other agencies.))

Take action. The next time someone asks you, “what do you mean by X?”, make a note of it, go back to it later, and write your own definition. Or definitions. You may answer the question not just for your audience but for yourself.

My best,

Rowan -

Hot day at the beach in Scandinavia

The most theatrical sauna I’ve been to seats about 80 people and requires, by custom, silence – unless you have a poem or verse memorized and would like to recite it. That’s the tradition at the Oregon Country Fair’s private sauna for staff.

That happens in the Summer but as I write this, it’s the middle of Winter – where in the US do you go for a hot day at the beach (besides Florida or Hawaii)? You might go to a sauna. It’s not the beach on a hot day, but in some ways, it’s better. The acoustics are better for reciting verse, for example. There are other advantages but the point is that rather than being a weak imitation of the beach on a hot day, the sauna is something different, with its own merits.

As we move into a digital era, riding the coattails of digital marketing and other online efficiencies, we have to look for parallels to the sauna vs hot-day-at-beach dynamic.

In the realm of psychotherapy, therapists who are used to delivering their services in-person experiment with “teletherapy” delivered over the phone or video (quite different experiences).

As with remote consulting and online learning, our initial assumption was that neither party needing to travel was the primary value driver of teletherapy. And it perhaps still is. Online therapy has been seen as a convenient but lower-value version of in-person.

But therapists and their patients discover ways to embrace online therapy and discover its merits. Just as all of us can embrace the benefits of online consulting, down to its most minute details:

- A phone conversation can be more revealing than an in-person meeting (or a video conference).

- A video conference can bring people’s faces closer together than during an in-person meeting

- It is more natural to record online audio/video conferences than in-person meetings; together with improving transcription services, online consulting creates resources that can be revisited and mined in ways that meetings cannot be

- Online meetings come with the ability to easily share computer screens back and forth – and links sent in chat

- Online meetings can fairly easily scale to 15 or even 150 people, using a product like Zoom at least, the upper end of which is very difficult to achieve in-person

- Using the right audio technology – on both ends – we can actually make ourselves heard and understood more easily than in many typical in-person venues

Of course, phone and online meetings can also be disastrous in ways that exceed even the worst in-person meeting. Especially if you don’t practice them.

Jason Fried has said that if you’re going to start a remote company, at least 50% of your staff should be remote. In other words, you don’t want an almost entirely in-person workforce with a couple of outliers on the horizons. They’ll be isolated because the rest of the team won’t know how to communicate with them.

It’s the same with therapists and consultants who primarily do their work in-person. If they use the Internet as an afterthought or special use case, they won’t develop the necessary skills to turn it into a sales and marketing asset, not just a pale imitation of the so-called real thing.

My best,

Rowan -

What if you live to 150?

In her book, Why Him? Why Her?, biological anthropologist ((anthropologist = apologist for humankind? #lexicographypuns)) Helen Fisher asked this question:

“What will courtship, mate selection, family composition, and networks be like when we are all living for 150 years?”

To which my first response would be, What did these things look like when we were all living for 35 years? But maybe that’s because I just laid eyes on the classic, Sapiens, a highly narrative rendition of prehistoric human history. Clan of the Cave bears, except Jean Aul is a scientist. In Sapiens, you find the earliest examples of technology consulting, marketing, and team-based business development – if you squint hard enough.

Meanwhile, marketing and business development authority Blair Enns, has pledged never to retire, to die “with this boots on”, deeply enmeshed in his work. In his words:

“I now see the idea of retirement, in this age of the knowledge worker, as destructive. It causes us to put up with less than ideal circumstances today as we wait for our reward in the end, except the idealized reward of the retired life isn’t really what most of us want.” ((Only linking to this because it’s hard to find in search https://www.winwithoutpitching.com/no-exit/))

This represents a return to our prehistoric life-work approach, and I’m inclined to agree with Blair on this point; maybe that’s because my own dad is setting the example for me, continuing his life’s mission into his 80’s.

But Blair maybe has different reasons than his caveman ancestors to endorse “unretirement”: his work is his mission. He believes creative people should get their due in exchange for their contribution to creating value in the business world.

Now, I am not telling anyone when to retire or not to retire.

But one takeaway from this is to think of your work as a long term mission and your marketing as the detailed explanations of what that mission is all about, why it exists, where it’s going. But the other takeaway is that we have time to make that mission happen. We have time to – and maybe you saw this coming – develop long-term content and content marketing strategies.

The job of the content marketing strategy is to help the current and future state of your business get better clients. It’s hard work and a lot of work, but less so if you divide up over several years.

This brings me to my second response to Helen Fisher’s question, “What will our life work, and our strategies that communicate it, look like when we are all living for 150 years?”.

Probably won’t look like “top 10 this” and “top 10 that” listicles and spending 2% of your annual revenue buying Facebook ads.

I think it’ll be easier to get a sense of what this means if I show you what a content marketing strategy actually looks like in practice. In my next post, I’m going to bring this discussion back down to earth a little bit and explore the anatomy of a content marketing-focused editorial calendar.

Yours truly,

RowanPS. Programming note – going to be off work for a few days, so you’ll not hear from me until Monday! In the meantime, I’d love to hear from you 🙂

-

Empathy, Curiosity & McKinsey

At one point in my life, my semi-tongue-in-cheek career ambition was wandering mendicant. Never achieved that goal, but who knows what life has in store.

Anyway, I think maybe I was inspired by fellow wanderer Paul Theroux, the prolific travel writer who gave us so many books, some of which you may know as movies: The Mosquito Coast, The Old Patagonia Express, The Great Railway Bazaar, and my personal favorite, Dark Star Safari. Among about 15 other excellent foreign culture immersion novels.

But it was in a book of short stories, The Consul’s File, where Theroux described his 2-year stint in the foreign service, working as a consul at various US embassies and consulates across Asia. (Consuls – if you’ve ever lost your passport in a foreign country, you’ve met one of these lovely people).

But how did a nomadic travel writer get into the foreign service, normally a place for straight and narrow people? By taking a merit-based exam. For many decades, in fact, the sole requirement for admission to the foreign service was a lengthy, far-ranging, impossible-to-study-for examination of general knowledge about almost everything, including of course politics and history.

And that was it. There was no cover letter, no CV, no recommendations, no references, no university grade point average.

It was a curiosity test.

And by the most cogent accounts, it worked well.

Enter McKinsey & Company, stage left. McKinsey & Company, consulting firm to businesses, governments, non-governmental organizations, non-profits, and organized crime. Hehe, just threw that last one in there to see if you were paying attention.

In the early 2000’s, the State Department’s then-boss, Condaleeza Rice, hires her former employer McKinsey to … help the State department achieve its goals. Result: abolishment of the US government’s only merit-based hiring process.((Good arguments were made for and against… or good spin, at least https://www.nytimes.com/2006/12/17/weekinreview/17lewin.html. But the title of the report, “Rarely Win at Trivial Pursuit? A Door Opens” is way off. The foreign service exam did not test for “trivial” knowledge; it tested for the kind of knowledge acquired by a curious, well-rounded, well-read person))((Want to take a mini pre-2006 foreign service exam? https://www.nytimes.com/2002/04/14/education/pop-quiz-foreign-service-exam-politically-correct.html)) Now it matters where you went to school, who you know, what your last name is, and how academically productive you were from roughly 14 to 22. Thank you, Bush administration.

Now, I know this isn’t the end of the world. Nor is McKinsey or institutional management consulting inherently bad. After all, McKinsey’s stated mission is to help their clients achieve their goals. Maybe it was the State department’s goal to re-introduce nepotism into its hiring. Or – more likely – screen for harder workers (which they can do, now that they can look at grade point averages).

There’s nothing wrong with hard work – especially when you’re an adult. Bouts of very hard work in marketing are essential. It is almost impossible to refine the three most important implementation skills in marketing – writing, visual/spatial design, and market research – without the mind busting bouts of effort that propel skill-breakthroughs. It’s one of the ways you level up.

But hard work is table stakes for a thousand and one professions. And quite frankly hard work tolerance is not important for State department employees. I’d say levelheaded-ness, an open mind, and yes, curiosity, matter more – you must understand intimate problems arising from multiple alien cultures well enough to take actions that have a big impact on the lives of strangers.

Same in my profession. When I hire a copywriter to work on a campaign for my own business, the quality that matters is curiosity about people.

In a sense being curious is a professional skill because you have to be judicious or you’ll end up wasting time. You don’t get to ask those same 40,000 questions you asked from ages to 2 -5, let alone repeat yourself.

It’s easy to dismiss marketing curiosity as stalker-ish. That’s what terms like demographic and psychographic evoke. And yes, Cambridge Analytica and Facebook do dirty deals that leverage private information to create fortunes and – it appears – let one government interfere in the elections of another.

But demographic curiosity is powerful tool in marketing, especially when infused with empathy.

Here’s how a recent exchange went with my client:

Questions: “So you’re sending this product orientation deck to people who work at universities? Which exact universities and what do they have in common? What departments or units? What are these people’s titles and how long in that role? How do you get a job like that – and why? What would make them feel good about their work at job? How do they want to feel? If you want to help them feel that way – how will your product do that?”

Conclusion: “Now we write down those answers, except frame them in a way that equips these people with arguments – for trying your solution – that they can take to their colleagues on your behalf“.

There’s more to it than that – it’s even better to examine each question in detail, in content than to briefly address them deck.

But the point is that empathetic curiosity has business value.

And I hope the foreign service continues to cultivate that quality, despite the abolition of the great curiosity test.

Warm regards,

Rowan